Feast of Booths (Sukkot)

Sukkot, the most important biblical fall festival, originally celebrated the end of the harvest season and offered an opportunity to thank God for the bountiful harvest through various rituals.

Sukkot, the most important biblical fall festival, originally celebrated the end of the harvest season and offered an opportunity to thank God for the bountiful harvest through various rituals.

Why is this festival called Sukkot?

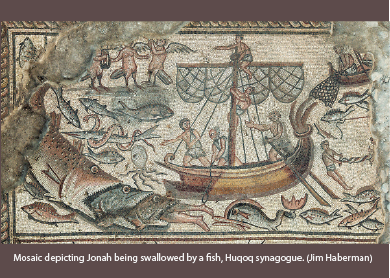

A sukkah (plural sukkot) is a booth—a temporary hut. It could have many functions. For example, it could provide protection from the blazing sun (Jonah 4:4 ) or be set up in the fall harvest season so that the workers could guard the crop that had been picked. Living in these huts also allowed the workers maximum time in the field. It is this type of structure, mentioned in Isa 1:8 (“And daughter Zion is left like a booth [Hebrew sukkah] in a vineyard”) that gave this fall harvest festival the name found in Deut 16:13 : “You shall keep the festival of booths [Hebrew sukkot] for seven days, when you have gathered in the produce from your threshing floor and your wine press.” Earlier biblical texts called this festival, “the festival of ingathering at the end of the year” and was commemorated “when you gather in from the field the fruit of your labor” (Exod 23:16 ).

According to Lev 23:33-43 , Sukkot was celebrated for seven or eight days in the fall, beginning with the fifteenth day of the seventh month (Tishri), soon after Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur; these three festivals together formed a complex of fall holidays, where Sukkot became closely associated with the upcoming rains, so necessary for a viable crop in the winter (see Zech 14:16-17 ). Lev 23:40-43 associates two main rituals with this festival: taking a special collection of agricultural products (“the fruit of majestic trees, branches of palm trees, boughs of leafy trees, and willows of the brook”) and dwelling in sukkot for the duration of the festival. In Neh 8:14-17 , these commandments are combined: the booths are made from these agricultural products. In later rabbinic law, as in the New Testament (John 12:13 , which originally referred to Sukkot rather than Passover), these goods are taken in hand and used for prayer.

What other elements were associated with the festival in the biblical period?

Sukkot was the festival of joy par excellence; as Deut 16:14 mandates, “Rejoice during your festival, you and your sons and your daughters, your male and female slaves, as well as the Levites, the strangers, the orphans, and the widows resident in your towns.” This was because the festival marked the end of the busy agricultural season that began with the late fall and early winter rains: having collected the crops, it was possible to relax for a few weeks until the rainy season and the planting and harvest seasons started again. It was a time to thank God for the past bounty and to hope and pray for rain that would allow the crops to flourish in the following months. In many circles in the biblical period, Sukkot was more important than the preceding Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur; it was so significant, that it is called “the festival” (Deut 16:4 ; 1Kgs 8:2 ), and the dedication of Solomon’s temple was imagined to have transpired on Sukkot (1Kgs 8 ).

At some point late in the biblical period, Sukkot became partially unmoored from its agricultural roots. Like other originally agricultural festivals, the festival became historicized, that is, connected to Israel’s sacred history. In the words of Lev 23:42-43 , “You shall live in booths for seven days; all that are citizens in Israel shall live in booths, so that your generations may know that I made the people of Israel live in booths when I brought them out of the land of Egypt.” But this shift in emphasis away from agriculture and to sacred history did not obscure the joyous underpinnings of the festival, which are further developed in rabbinic texts and continue until this day. In New Testament times, the lulav (palm branch) and etrog (citron—related to a lemon) became significant symbols of Judaism, depicted in Jewish coins and other objects of the first centuries CE.