The stories of Hagar and Ishmael have captured the attention of many readers from different cultural locations. Christian Egyptian readers of the Hebrew Bible have responded to the narrative of Hagar, the Egyptian maidservant of Sarah the Hebrew, in particular and interesting ways.

Many Egyptian Christians avoid identifying with Hagar and her son Ishmael, preferring instead to side with Sarah and her son Isaac. This decision is shaped by two attitudes that approach the narrative through sets of binary opposites. First, the story of Hagar has a long history of allegorization: in Galatians 4, Paul associates Hagar negatively with the law and Sarah positively with the promise. Second, the conflict and enmity between Muslims and Christians also affect the reception of the Hagar stories among Christian Egyptian communities. Although the social location of the oppressed and cast-out Hagar and Ishmael can be compared to that of Egypt’s marginalized Christian minority, their rejection of these two figures functions in a subtle way as a posture of resistance to the Muslim majority, who trace their traditions back to Hagar and Ishmael.

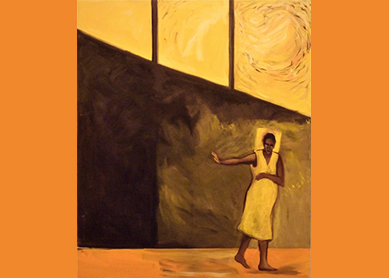

Christian Egyptian readers of the Hagar story might learn from postcolonial theory, which, by problematizing simple binaries that construct the self at the expense of the “other,” opens the door for mixed or hybrid identities. Rather than dismiss the Hebrew Bible because of its negative portrayals of Egypt or allegorize it to repress the political facet of identity, Christian Egyptians are invited to read the story of Hagar from their cultural location, holding their political and religious identities in a creative tension. Such a reading invites the community to critique its abuse of power when it marginalizes others, and also to recognize gifts of freedom that gush forth in the wilderness of oppression.

If the predominant image of Egypt in the Hebrew Bible is of slavery, we find a reversal in the story of Hagar, as Sarah, ancestor of the Israelites, afflicts an Egyptian woman. Though this reversal does not undo the oppression that the Israelites experienced in Egypt, it destabilizes the idea of Egypt as only a site of oppression. The same verb “to afflict” (Hebrew, ‘nh) that is used to describe Sarah’s affliction of Hagar (

A rereading of the story of Hagar and Sarah that offers Christian Egyptians a way to speak against their marginalization while avowing their political identity as Egyptians could have a ripple effect. What other privileged and powerful community members might be held accountable, as Sarah and Abraham should be, because of their gender, social status, or abuse of power?