Reading the Bible can seem like reading history, as many biblical narratives appear to recount past events. But is the Bible really a book that reports the past “as it actually happened”? Until relatively recently, the answer to that question would have been “yes.” After all, if the Bible is God’s word, wouldn’t it be accurate? But since the nineteenth century, and even earlier, biblical scholars have identified pervasive problems with this understanding of the relationship between the Bible and history.

The first problem is that the discoveries of modern science contradict biblical texts. Astronomy and biology show that the origins and development of the world and its inhabitants were part of a long, complex, and ongoing process that cannot be reconciled with Gen 1. Geological evidence rules out the possibility, suggested in Gen 6-9, that the entire earth was covered with water in the eons since human life began.

The second major problem was caused by the results of archaeological excavations that have challenged the historicity of many biblical narratives. For instance, excavations of Jericho and Ai show that neither city existed at the time of Israelite beginnings; the dramatic conquest stories of Josh 2-6 and Josh 7-8 cannot be taken at face value.

Other problems emerged with the study of the Bible itself. The growth of information about biblical languages and literary features led to the realization that biblical narratives about ancient Israel reached their final form many centuries after the events they describe. The narrators were not eyewitnesses to events they recount. Rather, they drew upon a variety of legends, traditions, folktales, and other materials that can no longer be identified; but few of these sources can be considered factual. Close study of biblical narratives revealed that they are replete with inconsistencies and even outright contradictions. For example, humans are created before vegetation in Gen 2:4-9 but afterward in Gen 1:11-27. Or in 1Sam 17:50, David kills Goliath, whereas in 2Sam 21:19, Elhanan does. On a larger scale, the book of Joshua proclaims that the Israelites conquered “the whole land” (e.g., Josh 10:40), but the book of Judges describes the survival of many Canaanites and other peoples.

One other issue is that many “events” recounted in the Bible are said to have been God’s acts. The exodus account, for example, proclaims that “the Lord drove the sea back … and the waters were divided” (Exod 14:21), enabling the Israelites to cross the Reed Sea. Statements of this kind can be neither verified nor disproved. They are interpretive statements, not historical reports.

Understanding biblical narratives thus means setting aside the notion that all of what the Bible says is factually “true.” The way people in biblical antiquity accounted for their past is not the same as it is in the modern world. Nowadays we expect “history” to provide an accurate narrative of real events, though we still realize that any two eyewitness observers of an event will recall it in different ways, depending on their individual interests and prior beliefs. But this is a relatively new approach, one that was not present when biblical narratives took shape.

Like other ancient storytellers, the shapers of biblical narratives were not concerned with getting it factually right; rather, their aim was to make an important point. Their narratives could serve many different purposes, all relevant to their own time periods and the audiences they were addressing. They might take a popular legend and embellish it further—the better the story, the more likely that people would listen and learn. They used a variety of sources plus their own creative imaginations to shape their stories. Think of all the quoted speech in the Bible. There were no mobile electronic devices to preserve the words of biblical figures. The speeches and utterances of biblical characters are what the narrator believes would have been said, given the circumstances depicted. Biblical narratives were all about learning from the past, even an “invented” past. David’s prominence is made known through tales of heroic deeds, just as George Washington’s honesty is presented by the cherry-tree incident. The facts were not the issue; what could be learned from the stories was paramount.

Does this understanding of the historicity of biblical texts mean that they are devoid of any validity? Absolutely not. Authentic experiences and events surely underlie many biblical narratives. Archaeology may call the historicity of some texts into question, but it can also indicate the general veracity of others. For example, Israelite beginnings in the land may not be the result of the military events described in Joshua, but the burgeoning of small settlements in the hill country at the beginning of the Iron Age likely reflects the emergence of the population eventually identified as Israelite. Archaeological discoveries can also authenticate specific events and people. The Mesha Stela, a ninth-century B.C.E. inscription found in Jordan, mentions the biblical king Omri and the Moabite ruler Mesha; it also reports that Omri had oppressed the Moabites. These features resonate with certain—although not all—aspects of the narrative in 2Kgs 3. The texts and monuments of other ancient Near Eastern peoples also contain information that correlates with some biblical texts.

Although most of Genesis belongs to the realm of myth and legend, historical events and characters may be reflected in many other biblical narratives. Each episode must be examined in relation to other sources, both archaeological and textual; and its literary features must also be taken into account. The larger strokes of Israelite history may thereby come into view, but it is likely that relatively few of the narratives can ever be considered history “as it actually happened.” Perhaps the best way to approach the Bible in relation to history is to stop asking whether or not it is true and rather to consider what truths its stories tell.

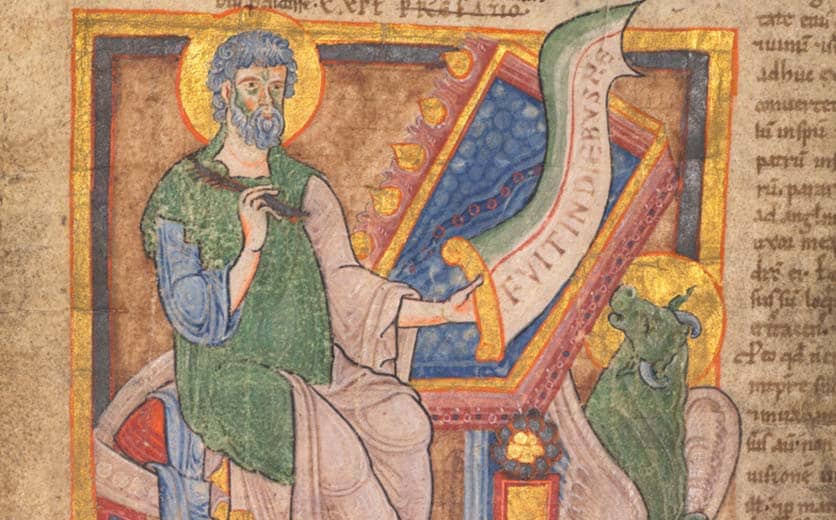

Image Credit: Miniature from a Latin Bible: St. Luke. Ink, tempera, and gold on vellum. 6 13/16 x 6 5/16 in (cropped). Courtesy the

Cleveland Museum of Art.