Due to his controversial antislavery role, John Brown (1800–1859) has often been excluded from the history of nineteenth-century US evangelicalism. However, his impact on the nation was substantial, especially after his execution by proslavery authorities in Virginia. Brown’s jail letters and published interviews reveal a depth of biblical commitment and demonstrate that he was a conscious heir of the Protestant Reformation and a radical reformer rather than a revolutionary.

Who was John Brown?

Brown was a strident abolitionist from northeastern Ohio with roots in the Calvinist tradition. Having acknowledged Christian faith in his youth, Brown considered the pastoral ministry for a time and even went east to study. However, a chronic inflammation of his eyes and his uneven schooling proved too disadvantageous, and he returned west to take up the life of a tanner, livestock specialist, and sheep farmer. Brown continued his studies privately, and an unabashed commitment to the Bible as God’s inspired and infallible word was a prevailing theme in his life thereafter. As a young adult, Brown founded a Congregational church in northwestern Pennsylvania. Over the years, he taught Sunday school in various places, occasionally also serving as a lay preacher.

Why was John Brown executed, and how should he be remembered?

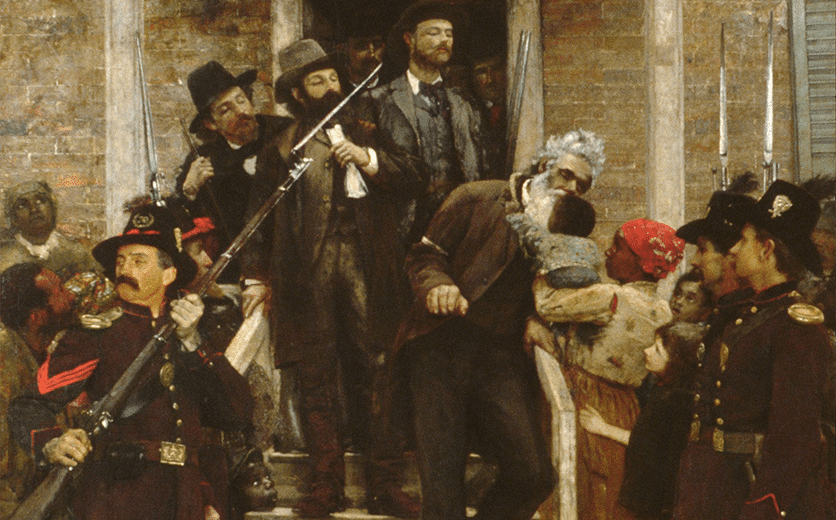

Along with his honesty and hard work, John Brown’s opposition to slavery was part of his lifelong reputation. He was not alone. Although abolitionism was largely dominated by religious people in Brown’s era, their opposition to slavery was increasingly based on modern ethical arguments while Brown’s opposition remained firmly dependent upon a traditional reading of Scripture. His stance grew even more zealous in the 1850s as the nation moved toward irreconcilable differences between anti-slavery and pro-slavery factions. When his sons emigrated to the newly opened Kansas Territory in 1855, Brown joined them. There, he observed that the slaveholding interests in the area were prone to use violence to extend slavery. Brown attempted to avoid outright insurrection, but he also used force, in his case to protect enslaved people and provide opportunities for them to escape. In 1856, after an army of Missourians invaded the territory and assaulted the free-state town of Lawrence, Brown and his sons took violent action against agents of the proslavery court. While sometimes characterized as a terrorist himself, Brown viewed his actions as necessary wartime measures to protect his family and others against the illegal violent actions of the proslavery regime. Three years later, in 1859, Brown tried to launch an armed version of the Underground Railroad in western Virginia in the hope of destabilizing slavery throughout the South. Failing to initiate his plan at Harper’s Ferry, he was tried by a proslavery court and hanged.

While a prisoner, Brown wrote a series of letters and conducted several interviews, which were then widely published. The content of these letters and interviews was far more expressive of biblical piety than abolitionist propaganda. Brown vigorously argued that slaves were entitled to freedom since they too were made in God’s image. He also argued that the operations of slavery were biblically sinful. As a postmillennialist, Brown seems to have believed that slavery was hindering the expansion of the gospel and the return of Christ. When some of his adult children expressed skepticism toward the Bible, Brown admonished them to trust in Christ and lean upon the Bible as an anchor and compass for their souls. Before hanging, Brown bequeathed money to purchase Bibles for his children and grandchildren and gifted his jailhouse Bible to one of his jailers, believing his voice in history was far less important than the words of Scripture. Still, Brown’s words inflamed the North, incited the South, and framed the religious sensibility that overhung the nation throughout the Civil War.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Brown’s reputation was demeaned by Southern writers and conservative Northerners backpedaling from the short-lived era of Reconstruction. However, well into the twentieth century, he was remembered as an inspiring and admirable Christian figure by many Christians, not the least of which was the celebrated British pastor, Charles H. Spurgeon, who once wrote that Brown was “immortal in the memories of the good in England,” adding “in my heart he lives.”

What is significant about John Brown’s Jailhouse Bible?

Those who observed or visited Brown in jail typically observed his devotion to daily Bible reading. The copy of the Bible he used in jail was the King James Version of 1611, printed by the American Bible Society of New York. It was 6 x 4 inches with a brown leather cover. His reverence for the Bible prevented him from writing on its pages. However, he intentionally folded page corners to mark texts pertaining to slavery, justice, and the gospel and also set off verses using ink lines that look similar to modern parentheses. Brown knew that his biblical readings would be published, as they indeed were after his death in the popular New York Illustrated News, and his intention was to make a case for his controversial actions and present his final witness on behalf of the anti-slavery cause. The only actual writing in the book is an inscription that declares: “There is no commentary in the world so good in order to a right understanding of this blessed book as an honest Childlike and teachable Spirit.” John Brown’s Jailhouse Bible is today held by The Chicago History Museum.