Much of the Hebrew Bible struggles with the question: where is God to be found? For some, YHWH is found in the sanctuary (

God’s presence was felt to be protective, healing, even awe-inspiring, as we hear in

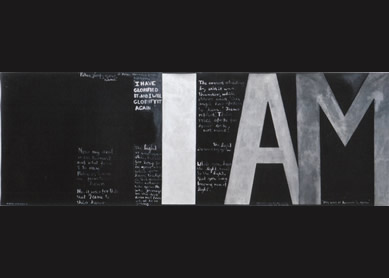

For some, YHWH’S enormity and exclusivity meant that the deity could be present anywhere but, also, strangely, that it was simultaneously elusive, since it was not constrained by graven images or limited to the Temple. Isaiah of Jerusalem’s call narrative grapples with these complexities. Standing within the Temple, Isaiah sees YHWH “high and lifted up”; he can see only the bottom edge of the deity’s robe, suggesting the high holiness of YHWH’s regal being, above and out of reach (

While God’s presence was often terrifying to witness, it was more terrible to grapple with the possibility of God’s absence—that God had turned away in anger, or that God had forgotten the plight of the people. The Bible preserves a painful record of this experience, as when the Psalmist cries out, “O Lord, why do you cast me off? Why do you hide your face from me?” (

The book of Job wrestles with these anxieties about God’s absence, even as it reckons with the terrifying implications of God’s presence. In the opening chapters, YHWH meets with the divine council in the heavenly abode, and unbeknownst to humankind, resolves to deliver a devastating blow against righteous Job. Job and his friends, not knowing this, debate God’s presence, absence, thoughts, actions with no input from the divine realm. Job feels both bereft when God does not intervene on his behalf and also plagued—pursued with a vengeance, even—by God. Finally, God shows up to deliver powerful but enigmatic words from a whirlwind (

As we might expect from a collection of literature that comprises a broad time period and a diversity of thinkers, the Hebrew Bible encompasses rich and varied perspectives on divine presence and absence. It would be a mistake, in other words, to think that the Bible has one position on God’s presence—or that the Bible alone tells the whole story of ancient Israel’s experience. The enduring richness of the Bible’s reflections on YHWH’S presence may indeed come from the broad array of voices that comprise the Hebrew Bible and engage this question in their own time and place, on their own particular terms.

Bibliography

- Niditch, Susan. Ancient Israelite Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Smith, Mark S. The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel. 2nd ed. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 2002.

- Stavrakopoulou, Francesca, and John Barton. Religious Diversity in Ancient Israel and Judah. New York: Bloomsbury/T&T Clark, 2010.