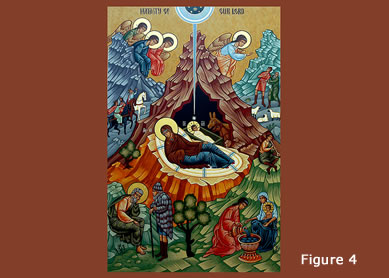

Jesus’ birth is one of the best-known Bible stories. So it can come as a surprise to realize that it only appears in two Gospels, Matthew and Luke. And their stories are quite different. Only Matthew has a star, wise men, King Herod, and the slaughter of the toddlers in Bethlehem. Only Luke, in the passage under discussion, has a census, a stable, angels, and shepherds. Most scholars date these texts to 80-100 C.E., and they assume that by this time the precise details of Jesus’ birth had been forgotten.

What the infancy stories do is set up the story of Jesus in each Gospel, reflecting the interests and theology of each writer. So Matthew presents Jesus as a royal figure whose birth is signaled in the heavens; foreign visitors point ahead to the spread of the message to all nations (Matt 28:19); and Herod’s slaughter of the infants recalls the actions of Pharaoh in Exodus, subtly casting Jesus as a new Moses. Luke’s birth story illustrates two of his interests: a concern to show that Jesus came for the poor (hence his humble surroundings and the visit of the shepherds) and a fondness for linking events in Christian history with wider events on the world stage. But are there no historical facts behind Luke’s story?

Was Jesus born in Bethlehem?

Despite their differences, Matthew and Luke both agree that Jesus was born in Bethlehem. In Matthew, the holy family lives there already, so the author of this Gospel has to explain why they eventually settle in Nazareth—which he does by the story of Herod’s massacre and his son Archelaus’s cruelty (Matt 2:13-23). In Luke, the family lives in Nazareth, and this author has to bring them down to Bethlehem for Jesus’ birth, which he does by means of a census (Luke 2:1-5).

Bethlehem, of course, was not any old town. Ten kilometers south of Jerusalem, it was the ancestral home of King David (1Sam 17:12). God made a covenant with David and a belief developed that a future, messianic king would be from his house (Ps 89:19-37, Isa 9:2-7, Isa 11:1-9, Ezek 34:23-24). So Bethlehem came to be seen as the birthplace of the Messiah (see especially Mic 5:2, a passage quoted in Matt 2:5-6). To claim that Jesus was born in Bethlehem, then, was a clear attempt to proclaim him as David’s son, the longed-for Jewish Messiah.

But how historical is the Bethlehem tradition? Surprisingly, perhaps, no other New Testament text mentions it: there is nothing in the letters of Paul, our earliest Christian writer, and nothing in Mark, our earliest Gospel. Even stranger, perhaps, is the Gospel of John’s curious silence, even when Nathaniel flippantly asks if anything good can come out of Nazareth (John 1:46)—surely the perfect cue for the true story of Jesus’s birth. There is good reason to suppose, then, that even if the Bethlehem tradition predated Matthew and Luke, it was unknown to many of the earliest Christians. While this does not prove that the tradition has no factual basis, it seems more likely that the story was developed within early Christian circles to connect Jesus with the Davidic Messiah.

Was there really a census?

Yes—it was carried out by Publius Sulpicius Quirinius, the capable legate of Syria (6-12 C.E.). When Herod I died in 4 B.C.E., his kingdom was divided among three of his sons, and the largest section (Judea, Samaria, and Idumea) was given to his son Archelaus. After ten years, however, Archelaus was deposed and the emperor Augustus decided to transform the territory into a Roman province, ruled directly by a Roman prefect. The census was taken at this point, in 6 C.E., to allow Rome to work out what each resident should be paying in tax.

Luke’s account contains a number of inaccuracies: the census didn’t include “all the world” (Luke 2:1), it didn’t involve Galilee, and people would have registered at their usual homes (not those of their ancestors). Furthermore, if historical, Luke’s account would contradict Matthew’s clear indication that Jesus was born shortly before the death of Herod I (that is, around a decade earlier, in 6 B.C.E.). Attempts to suggest that Luke’s reference to the “first registration” (Luke 2:2) was an earlier census carried out by Quirinius have not been successful.

In all probability, the earliest Christians did not know exactly when Jesus was born. At a time when there were no birth certificates or easily accessible records, this would not be at all surprising. Both Gospel writers wove their stories around memorable events from roughly the right period: Matthew made use of a star (or a planetary conjunction) and the death of Herod, while Luke connected it with the census of Quirinius. This fits with his tendency to associate the Christian story with wider world events (other examples include the world famine in Acts 11:28 and Claudius’s expulsion of Jews from Rome in Acts 18:2). Luke’s message is clear: far from opposing the new Christian movement, the Roman Empire provided the framework under which it could flourish.