The Gospel of Matthew opens with “an account of the genealogy of Jesus the Messiah” (Matt 1:1, NSRVue). Tracing Jesus’s family tree back to Abraham, this account supports Matthew’s claims that Jesus is Israel’s Messiah, God’s anointed. Careful readers, however, have long noticed a curious detail: in an otherwise patrilineal list of ancestors, this genealogy includes four women from the Hebrew Bible (Tamar, Rahab, Ruth, and Bathsheba) as well as the mother of Jesus. Explanations of these women’s inclusion often look for common threads in their stories, interpreting these patterns as precedent-setting for Jesus’s birth or ministry.

What do we know about these women?

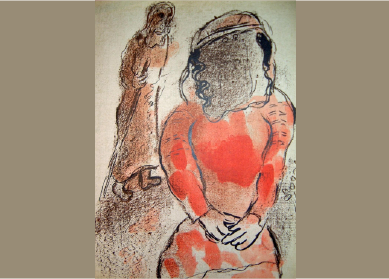

All of the women in Matthew’s genealogy were in vulnerable positions. Whether through their own wits or their openness to God’s plans, however, they secured a future for themselves and their children. Tamar, daughter-in-law of Judah, was twice-widowed and childless. In Gen 38, she disguised herself, seduced her father-in-law, and conceived twin sons. Judah accused her of promiscuity, but ultimately even he recognized her as righteous. Rahab was a Canaanite prostitute, who was approached by Israelite spies (Josh 2, 6). By securing their safety she secured a future for herself and her family among the Israelites. Ruth was a Moabite and a childless widow (Ruth 1–4). She provided for herself and her mother-in-law by spending the night with their relative, Boaz, on the threshing floor. They married, and, with him, she carried on the family line. Bathsheba was already married when King David ordered for her to be brought to him. When she conceived David’s child, he had her husband killed and married her. Their first child died, but Bathsheba later ensured a place for herself and her family through their second son, Solomon (2 Sam 11–12; 1 Kgs 1).

How might the inclusion of these women anticipate Matthew’s portrayal of Jesus?

Some interpreters suggest that the irregular or scandalous nature of these women’s sexual encounters sets a precedent for the irregularity of Mary’s experience ahead of the birth of Jesus (Matt 1). Matthew is certainly interested in communicating the irregular nature of Jesus’s conception by the Holy Spirit while his mother was a virgin. The author does so, however, in a way that emphasizes the unique and miraculous nature of the conception and deemphasizes its scandal.

Others see the women as foreshadowing aspects of Jesus’s ministry or the author’s community. If the women are considered gentiles, then their inclusion could set a precedent for gentile inclusion among Jesus’s followers. Tamar and Bathsheba, however, are not explicitly identified as non-Israelites in the Hebrew Bible, although they are remembered as such in some later traditions. Furthermore, even Rahab and Ruth are occasionally regarded as Jewish proselytes rather than gentiles per se. One might, then, understand them all more broadly as having been outsiders (ethnically, socially, etc.) who came to be insiders.

Another hypothesis—that these women were particularly sinful and were included to anticipate Jesus’s redemption of sinners—has unfortunately been persistent despite having no biblical basis. None of the women is remembered as sinful within the biblical tradition, especially not when compared to many of the men in the list (including Judah and David). Rather, all of them might be understood as victims of exploitative situations, who, nevertheless, persisted and carried on this family line.

Through their vulnerabilities and their outsider status each of these women joined and redefined this messianic family line. Their inclusion anticipates both Jesus’s birth and Matthew’s expanding definition of family within the early church.

Bibliography

- Brown, Raymond E. The Birth of the Messiah: A Commentary on the Infancy Narratives in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke. Rev. ed. New York: Doubleday, 1993.

- Levine, Amy-Jill. “Matthew.” Pages 465–77 in The Women’s Bible Commentary. Edited by Carol A. Newsom, Sharon H. Ringe, and Jacqueline E. Lapsley. 3rd ed. Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2012.

- Schaberg, Jane. The Illegitimacy of Jesus. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1987.