Every contract we sign has its stipulations—rules that we have to obey to avoid facing the penalties for breaking the contract. The same was true in the ancient Near East. The region’s surviving documents contain sale contracts, slavery contracts, marriage contracts, and adoption contracts, among others. Even city-states and nation-states could enter into contracts with each other. All of these contracts contained rules that bound the parties to certain obligations.

Most of the written records from the ancient Near East are contained on small clay tablets inscribed with cuneiform (wedge-shaped) writing. The vast majority of these come from Mesopotamia, inhabited by Assyria in the north and Babylonia in the south. Fortunately for us, clay was the medium of choice for recording writing in those areas, for clay, once it hardens or is baked, lasts for a very long time. Among the tablets that have been excavated in the region are thousands of contracts.

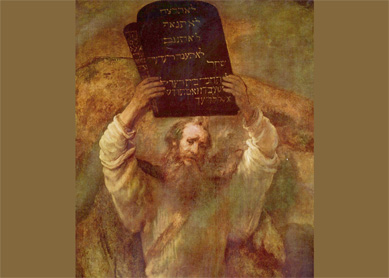

But what do contracts have to do with the Ten Commandments? Everywhere that the Ten Commandments are mentioned in the Hebrew Bible, they are associated with the idea of a covenant. The word “covenant” is merely a fancy word for “agreement” or, better yet, “contract” or “treaty.” The covenant in question, of course, is the covenant that the Hebrew Bible’s authors say was concluded at Mount Sinai (Horeb in some passages) between Yahweh (the LORD) and the people of Israel. Although this covenant is described in various ways, it is nicely summed up in

Both marriage contracts and adoption contracts use language that is nearly identical to that of the Sinai covenant. In some Aramaic marriage contracts from the biblical period, the groom states, “She is my wife, and I am her husband,” and the bride responds in kind. Babylonian adoption contracts often record the father’s oath, “You are my son.” These statements are performative—they actualize the relationship that is stated. Thus, the biblical authors portray Yahweh saying, “you are my people,” using the same kind of language that these other contracts use to enact the covenant with the Israelite people. In fact, we can say that the statement ascribed to Yahweh at Sinai is contractual language.

What role, then, do the Ten Commandments play in all of this? Long lists of rules were not common in contracts between individuals, but they were in treaties (contracts between states). Ancient Near Eastern treaties tended to follow a general format consisting of at least four parts: 1) a description of events leading up to the treaty; 2) the essence of the treaty (typically a commitment of loyalty on the part of the weaker party to the stronger); 3) a list of provisions and stipulations describing adherence to the treaty; and 4) a list of curses resulting from breaking the treaty. Within the Sinai covenant, the Ten Commandments form part of the “provisions and stipulations” section. They show what the biblical authors believed loyalty to Yahweh was supposed to look like. Together with longer lists of rules that are also associated with the Sinai covenant in the Bible, they specify the Israelites’ contractual—or, as some might prefer, covenantal—obligations, as understood by the authors who compiled these biblical texts.

Bibliography

- Miller, Robert D. Covenant and Grace in the Old Testament: Assyrian Propaganda and Israelite Faith. Piscataway, N.J.: Gorgias Press, 2012.

- Westbrook, Raymond, and Bruce Wells. Everyday Law in Biblical Israel: An Introduction. Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2009. See especially chapter 6.

- Burnside, Jonathan. God, Justice, and Society: Aspects of Law and Legality in the Bible. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011. See especially chapter 2.