Creation stories go right to the heart of human self-understanding. And they often focus on origins: of the cosmos and of humanity, and the relationship between the two. For example, do human beings stand at the pinnacle of creation, made in the image of Yahweh-Elohim? Or, following Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace, are humans, ha-adam, another branch in the evolutionary tree, made of earth, sharing blood and breath with kol nefesh, “every living creature that moves” (Gen 1:21)?

The most famous creation accounts occur in Genesis, where creation of both humans and animals actually happens twice and is closely connected. The first account compresses the creation and blessing of the whole swarming animal kingdom into a mere six verses (Gen 1:20-25). Afterward, female and male humans are made in God’s image and given “dominion” over every other living creature (Gen 1:26-28).

The second story reverses the sequence of creation, with Adam created first, before the animals (Gen 2:7). Here, God forms man from the dust of the ground and breathes life into “his nostrils.” Yet Adam is alone, and God decides to make him a “helper” from “every animal of the field and every bird of the air” (Gen 2:19-20); the creation of the animals in this story takes just two verses. Adam names each one but none are suitable partners, which leads God to create woman from Adam’s rib.

So what do these texts imply about the coexistence of humans and animals? For many scholars, the answer centers on the connotations of the Hebrew word radah (Gen 1:26). With its basic meaning of “treading or trampling down,” linked to kingly rule in the Hebrew Bible, radah is often translated as “dominion.” When this is coupled with the command in Gen 1:28 to “fill the earth and subdue it,” humankind seems divinely ordained to dominate the rest of creation. In a famous essay, “The Historical Roots of our Ecologic Crisis” (1967), Lynn White Jr. argues that Western Christianity’s reading of these passages has enabled humanity’s scientific and technological exploitation of the environment. As White notes, “[d]espite Darwin, we are not, in our hearts, part of the natural process” (p. 1206).

Others have suggested that this word dominion should be understood as a more benign rule or stewardship. Genesis 2:15 suggests that Adam is created to till and keep the garden in order, and some interpreters take this (with other verses) to suggest that humans are to be responsible stewards. In addition, many people interpret Gen 1:29 as emphasizing Adam and Eve’s vegetarian diet, with meat only becoming part of the table after Noah’s escape from the flood (Gen 9:3). However, in the second creation story, God also clothes the naked Adam and Eve with skins (Gen 3:21), hinting that some of the newly created animals might be used. The ambiguities surrounding humanity’s relationship with other animals continues throughout the Bible.

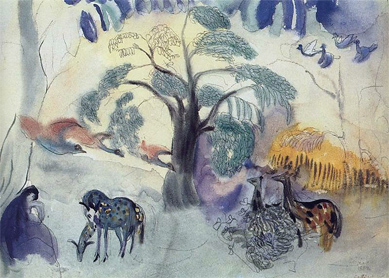

But more and more philosophers, theologians, poets, artists, and activists are attempting to reinsert humans back into the natural processes of the cosmos. In his sonnet “Naming the Animals,” Anthony Hecht tries to bring Adam (ha-adam) back down to earth (ha-adamah) and reimagine the relationship between the first man and the animals; for the poet, humility and humus (earth) are closely linked. Darren Aronofsky, the director of the film Noah (2014), claimed that Noah was the first environmentalist because of the part he plays in saving the animals. However you take this claim, God’s command to Noah in Gen 6:19 does echo the language used at creation in Gen 1:21. In Genesis, creation can only be recreated after the flood with all living creatures in attendance.

Perhaps imagining the humility of the ark, living cheek-by-jowl with “every animal of the field and every bird of the air” (Gen 2:19), might remind us of our very animality and help us recognize that we, too, are living creatures.