Anyone who reads the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John will likely notice the phrase “the Son of Man.” What may not be immediately apparent about the phrase is that Jesus is the only person who speaks the phrase. While Jesus’s disciples and others call him “Rabbi” or “Messiah” (Mark 9:5; Mark 8:29), Jesus calls himself “the Son of Man.” Many interpreters of the Bible have puzzled over what the phrase means and what Jesus or the gospel authors intended by its use.

Who or what is “the Son of Man”?

Asking who or what is “the Son of Man” is nothing new. For instance, the crowd in the Gospel of John asks Jesus “Who is this Son of Man?” (John 12:34). The answer to that question is more complicated than it might seem. The Greek phrase used in all four gospels (and Acts 7:56) is ho huis tou anthrōpou, which is typically translated as “the Son of Man.” Most interpreters think that this Greek phrase translates an Aramaic phrase like bar nash, which may be translated as “a son of man.” At their basic level, the Aramaic and Greek phrases are references to humanity. Someone who is a “son of man” is a human being. Throughout Israel’s Scriptures, similar phrases are used to speak of human beings (e.g., Gen 11:5; Deut 32:8; Ps 8:4; Eccl 1:13). The plural phrase “sons of men/man” is one of the most common uses, and God calls Ezekiel a “son of man” over ninety times (e.g., Ezek 2:1). Yet, nowhere in the Hebrew Scriptures do we have an example of “son of man” used as a self-reference or with the definite article “the” as in Jesus’s phrase “the Son of Man.”

What did Jesus mean by calling himself “the Son of Man”?

Since Jesus’s use of the phrase “the Son of Man” is distinctive, understanding what he meant by the phrase can be baffling. Interpreters have suggested numerous explanations throughout the centuries, as Delbert Burkett and Mogens Müller helpfully describe, yet the two most common views explain Jesus’s use of the phrase either as a particular idiom (the idiomatic view) or as an allusion to the “one like a son of man” in Dan 7 (the Danielic view). Those who hold to the idiomatic view argue that Jesus primarily used the phrase “the Son of Man” as a self-reference and that the idiom has no inherent meaning of its own. Thus, when Jesus used the phrase, he could have substituted the first person pronoun “I” (Matt 8:20), or Jesus was speaking about what is common to humanity (Mark 2:28). The idiomatic view easily explains how one gospel writer could use “the Son of Man” while another used “I” (compare Mark 8:31 with Matt 16:21). According to proponents of the idiomatic view, Jesus used the phrase to deflect claims about himself or to associate himself with humanity.

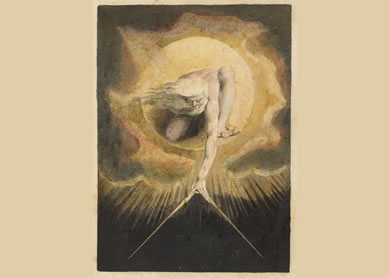

On the other hand, those who hold to the Danielic view understand that Jesus used the phrase to associate himself with the “one like a son of man” in Dan 7:13-14. In a vision, Daniel sees “one like a son of man” coming with the clouds of heaven to the Ancient of Days, and this human-like figure is given authority, glory, and a kingdom. The three Jewish apocalypses known to interpret this passage all present the son of man figure as a royal or messianic figure who will judge the wicked and redeem the righteous (see Parables of Enoch 46-48, Parables of Enoch 62; 4Ezra 13; and 2Bar 29-30; 2Bar 70-74). This Jewish apocalyptic interpretation suggests that Jesus used the phrase to identify himself as the “one like a son of man” from Daniel, that is, “the Son of Man.” When Jesus speaks to his disciples in Mark’s eschatological discourse, Jesus makes an explicit connection to Dan 7:13 with the use of Danielic language, namely, “coming with the clouds of heaven with great power and glory” (Mark 13:26; also Mark 14:62). According to proponents of the Danielic view, Jesus made veiled messianic claims when he called himself “the Son of Man.”

Both views have been the predominant view at one time or another during the last century, but because of increased study of Jewish apocalypses (i.e., 1Enoch, 4Ezra, 2Baruch) and Second Temple Judaism more generally, the Danielic view appears more plausible than the idiomatic view. Jesus most likely referred to himself with the distinctive phrase “the Son of Man” to associate himself vaguely with the Danielic figure.

Bibliography

- Müller, Mogens. The Expression “Son of Man” and the Development of Christology: A History of Interpretation. London: Equinox, 2008.

- Reynolds, Benjamin E., ed. The Son of Man Problem: Critical Readings. T&T Clark Critical Readings in Biblical Studies. London: T&T Clark, 2018.

- Burkett, Delbert. The Son of Man Debate: A History and Evaluation. SNTSMS 107. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.