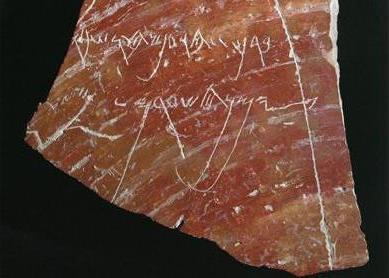

The Siloam Tunnel Inscription, discovered in 1880, narrates a dramatic moment in Jerusalem’s history. Fearing that the city would soon be under siege, residents thousands of years ago undertook a project that would bring water from a source outside the city walls into the city. The inscription, chiseled into the wall of a tunnel (called Hezekiah’s Tunnel) tells how two crews of workmen tunneled through bedrock. One started at the Gihon spring outside of the city; the other crew started from inside the city walls. Sometimes following natural fissures in the rock rather than always hewing through the stone (which accounts for the somewhat winding nature of the tunnel), the two crews finally met. It is this moment that the inscription, six lines of Old Hebrew, narrates:

(1) [. . .] the tunneling. And this is the narrative of the tunneling: While [the stone-cutters were wielding]

(2) the picks, each toward his co-worker,the picks, each toward his coworker, and while there were still three cubits to tunnel through, the voice of a man was heard calling out

(3) to his co-worker, because there was a fissure in the rock, running from south [to north]. And on the (final) day of

(4) tunneling, each of the stonecutters was striking (the stone) forcefully so as to meet his co-worker, pick after pick. And

(5) then the water began to flow from the source to the pool, a distance of 1200 cubits. And 100

(6) cubits was the height of the rock above the head of the stone-cutters.

(Author’s translation)

Biblical texts describing the reign of Hezekiah suggest the reason for this engineering feat. The Gihon spring is the source for the water that flowed through the Siloam Tunnel (

According to the inscription, the total length of the tunnel was around 1200 cubits. At about 18 inches per cubit, the total length was nearly 1800 feet. Modern measurements confirm that the tunnel is indeed almost 1800 feet long. At one point, the inscription states that the height of the ceiling is about 100 cubits (or 150 feet). Although there are places where the ceiling is about this high, there are also many places where it is less than six feet high. The inscription does not mention the breadth of the tunnel, but it is usually at least shoulder width.

Shortly after its discovery, the inscription was chiseled out and removed, with some resulting damage. Because its discovery and removal occurred during the Ottoman period, it was sent to Istanbul. It remains in the Istanbul Archaeological Museum.